Carmen Faye Mathes, University of Regina

Description

How does Romantic poetry capture what it means to work, labour or serve; to be productive or creative; to work for oneself or for others? Whether the choice to work is made freely or under coercion—including under threat of suffering, imprisonment or death—working is both transforming and transformative. Historical systems and sources of labour not limited to the Transatlantic slave trade, the Industrial Revolution, nascent understandings of the Anthropocene, and the rise of print culture will help us to contextualize expressions and representations of labour and laboriousness in the formal and stylistic interventions of poets and other writers in this period.

Background

I taught this graduate seminar to Honours and MA students (my university has no PhD program) in Fall 2022. I organized the course, week by week, to deliberately decenter Britain by bringing its transatlantic relations to the fore. Beginning with readings on colonial Jamaica; followed by the poetry of enslaved African-American poet Phillis Wheatley Peters; and only then moving to Abolitionist and Anti-slavery poetry written by white British poets, I designed this course to upend students’ assumptions about center and periphery. And it did. When we began the unit on Abolitionist poetry, students did not take for granted that the poets were white. Their equivocality in this regard reinforced for me the power of course design that destabilizes white authorship as the norm in Romantic-era literary studies.

The course concludes, rather than starts, by considering the dispossession caused by the enclosure of the common land and concomitant industrialization and urbanization in Britain. Near the end of term, during the period when students were preparing their final presentations and essays, we discussed present-day “affective labour” and gig capitalism.

Assignments

• In-Class Summary — 15%: Between Weeks 3 and 9, one or more student(s) per class will be responsible for writing and delivering 10-minute summaries of the academic articles that we are reading, and for prompting a short, in-class discussion by offering us two guiding questions.

• Research Essay Proposal — 15%

• In-Class Research Presentation — 20%

• Notework Journal — 15%*

• Final Research Essay — 35%

*A Note on “Notework Journal” Assignments

In designing this course, I tried to envision how a graduate seminar (about labour no less!) might encourage working together. Collaboration, coordination and the building of things both abstract, like shared concepts, and concrete, like physical timelines, became my pedagogical ambition for this course. In order to create the conditions for such collaborations, I asked students to complete specific activities prior to some of our weekly meetings, and to save them in a “Notework Journal,” which was collected and graded before the end of term:

- Week 2: Slavery in the West Indies Timeline

- Week 3: Class and Race Reflection

- Week 6: Maps

- Week 7: A Poet’s Family Tree

- Week 10: Questions for Our Guest Speaker

- Week 13: Affective Labour Reflection

Syllabus “Romanticism, Labour and Longing”

Schedule

Weekly Readings and Activities

| Content | Activity | |

| Week 1: Racial Capitalism | • Read: G. F. W. Hegel, selections from “The Master-Slave Dialectic” • Read: Karl Marx, “I. Bourgeois and Proletarians,” in The Communist Manifesto • Read: Cedric J. Robinson’s “Introduction” to Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition (1983) | |

| Week 2: On West Indian Slavery, Historical Overview (Jamaica as Case Study) | Please read the following in order, to help you envision changes chronologically: 1. Sections of A Description of the Island of Jamaica (1672) by Richard Blome: — “The Preface to the Reader” — Jamaica: “The Commodities, which this Island Produceth” and “Directions About a Cocoa Walk” (pages 8-23); “Some Considerations why his Majesty should keep, preserve, and support this Island” (54-63) — Barbados: “The Inhabitants” and “The maintenance of Servants and Slaves” (83-93) 2. Nuala Zahedieh’s “The Merchants of Port Royal, Jamaica, and the Spanish Contraband Trade, 1655-1692” The William and Mary Quarterly Vol. 43, No. 4 (Oct., 1986), pp. 570-593 (24 pages) 3. Jamaica: A Poem in Three Parts (1777), by an anonymous inhabitant of the island (Please read the three parts, pages 1-35, and don’t worry about the additional epistle) 4. Julius S. Scott, “Chapter 1: Pandora’s Box: The Masterless Caribbean at the end of the Eighteenth Century” in The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution (2018) | Create (for your Notework Journal): Based on the four readings, create a timeline of British involvement in the Caribbean, and in Jamaica in particular. Include any and all information that you feel is relevant, whether than information is political, historical, social, cultural or something else. A key part of the assignment is to record from where each piece of information comes. To that end, you could colour-code your timeline, include footnotes/citations, or develop some other method. Please bring your timeline to class. |

| Week 3: On Capitalism and Kinship | • Read: Jennifer L Morgan’s “Introduction: Refusing Demography” to Reckoning with Slavery • Return to: Jamaica: A Poem in Three Parts (1777), Part II: “Encomium on the Creole Ladies” • Read: Bryan Edward’s The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies of the West Indies (1794) (selections linked) • Read: Phillis Wheatley Peters’s “On Being Brought from Africa to America,” “Thoughts on the Works of Providence” and “On Imagination” in Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773) | Write (for your Notework Journal): According to Marx, “Our epoch, the epoch of the bourgeoisie, possesses … this distinctive feature: it has simplified the class antagonisms.” After revisiting Jamaica: A Poem along with Morgan’s and Wheatley Peters’s accounts, do you agree? How are race and class related to the emergence of racial capitalism in the 17th and 18th centuries? (400 words) |

| Week 4: On White Sentimentalism: Abolitionism vs. Antislavery Discourse | • Read: “The Sorrows of Yamba; or, Negro Woman’s Lamentation” (by Hannah More) • Read: “The Sorrows of Yamba; or, Negro Woman’s Lamentation” (by Eaglesfield Smith) • Read: Alan Richardson’s “‘The Sorrows of Yamba,’ by Eaglesfield Smith and Hannah More: Authorship, Ideology, and the Fractures of Antislavery Discourse” in Romanticism on the Net (2002) • Read: “Slavery” (also by Hannah More) | |

| Week 5 | Truth and Reconciliation Day: No Class | |

| Week 6: Sentimental Protests & Mapping the Transatlantic Slave Trade | • Read: “The Negro Girl” and “The Storm” (by Mary Robinson) • Read: “Pity for Poor Africans” and selections from The Task (by William Cowper) • Read: “The Firefly of Jamaica” (Charlotte Smith) • Visit: Slave Voyages Database: https://www.slavevoyages.org • Visit: Legacies of British Slavery: (https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/project/details) • Visit: Early Caribbean archive: https://ecda.northeastern.edu | Print (for your Notework Journal): After exploring the Slave Voyages Database and the “Maps” on both the Legacies of British Slavery website and the Early Caribbean Archive, choose one or two maps (related to the Transatlantic slave trade) to print out and include in your Journal. In class, you will give a low-stakes mini-presentation, describing your map, which we will then add to a collaborative world map. |

| Week 7 | • Read: “The Firefly of Jamaica” (by Charlotte Smith) • Visit: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography database • Visit: Legacies of British Slavery: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/project/details/ | Record (for your Notework Journal): Using the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, create a family tree, with the full names, birth and death dates, for immediate family members of last week’s poet, Charlotte Smith. Since most business records name male owners, you will want to pay particular attention to her male relatives. Aim to make your family tree as complete as possible. Based on your family tree, we will spend time in class exploring the Legacies of British Slavery website. |

| Week 8: Sentimentalism, Subverted | • Read: William Blake’s “The Chimney Sweeper,” from Songs of Experience • Read: Lily Gurton-Wachter’s “Blake’s ‘Little Black Thing’: Happiness and Injury in the Age of Slavery” ELH 87, no. 2 (Summer 2020), pp.519-552 • Read: William Blake’s America: A Prophecy (1793) | |

| Week 9: On Racial Capitalism’s Contemporary Reach | Watch: 13th (dir. Ava DuVernay) (feature length documentary) • Watch: “Geographies of Racial Capitalism with Ruth Wilson Gilmore” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2CS627aKrJI (approx. 20 min) • Read: Hortense Spillers’s “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” in Diacritics 17, no. 2 (1987): https://doi.org/10.2307/464747 • Read: Selected odes and sonnets from Poems Concerning the Slave Trade (by Robert Southey) | |

| Week 10: The Agricultural Revolution in Britain | Read: Ellen Rosenman’s “On Enclosure Acts and the Commons” BRANCH https://branchcollective.org/?ps_articles=ellen-rosenman-on-enclosure-acts-and-the-commons • Read: Oliver Goldsmith’s poem “The Deserted Village” (1770) • Read: William Wordsworth’s “The Female Vagrant” (1798) • Read: “Introduction: Whistling at the Plough” and “Chapter 1: A Day and a Half’s Work: John Clare and the Poetics of Laboring-Time” by Nathan TeBokkel | Question (for your Notework Journal): As you read Dr. TeBokkel’s introduction and chapter, highlight any phrases or sentences that jump out at you. Then, after you are finished reading, go back to those highlighted parts and develop at least three questions to ask him, which will help (1) clarify his arguments in your own mind, (2) develop our discussion about the agricultural revolution in Britain more broadly, and (3) help you as you work towards creating your own research essay. Record your questions in your Notework Journal prior to class, and be prepared to ask them when he visits our class! |

| Week 11: On Gleaning and Melancholy | • Watch: The Gleaners and I (Les glaneurs et la glaneuse) (dir. Agnès Varda) • Read: Wordsworth’s “The Solitary Reaper” and “The Leech Gatherer” • Read: Keats’s “Ode on Melancholy,” “Ode on a Nightingale,” and “To Autumn” • Read: Anahid Nersessian’s “Introduction” and chapters on “To Autumn” | Research Paper Proposals: due at the beginning of class! Today we will sign up for In-Class Presentations. Please have a look at your schedule, and choose a day that will suit you best. |

| Week 12: Working for the Good Life: An Introduction to Affect Theory | • Read: Introduction to the Affect Theory Reader, “An Inventory of Shimmers” • Read: Lauren Berlant’s “Cruel Optimism” (also in the Affect Theory Reader) • Read: Keats’s Isabella; or, the Pot of Basil | |

| Week 13: Affective Labour and the Loneliness of Capitalism | • Read: “Losing Steam After Marx and Freud” by Karyn Ball in Angelaki: A Journal of the Theoretical Humanities (2015) • Listen: “The E-Pimps of Only Fans” by Ezra Marcus (The Daily Podcast, NYTimes) • Define: “Affective Labour,” by reading: https://www.jamiewoodcock.net/blog/understanding- affective-labour/ | Write (for your Notework Journal): “What forms of affective labour do you produce? What forms of affective labour do you consume?” (400 words) |

| Week 14 | In-class presentations | |

| Week 15 | In-class presentations and peer review | |

| Week 16 | End of term! No classes | Final Research Essays due |

“West Indies Timeline” Notework Journal Activity

Building this timeline worked especially well for meeting my twin objectives of decentering Britain and encouraging collaborative learning at the honors/graduate level.

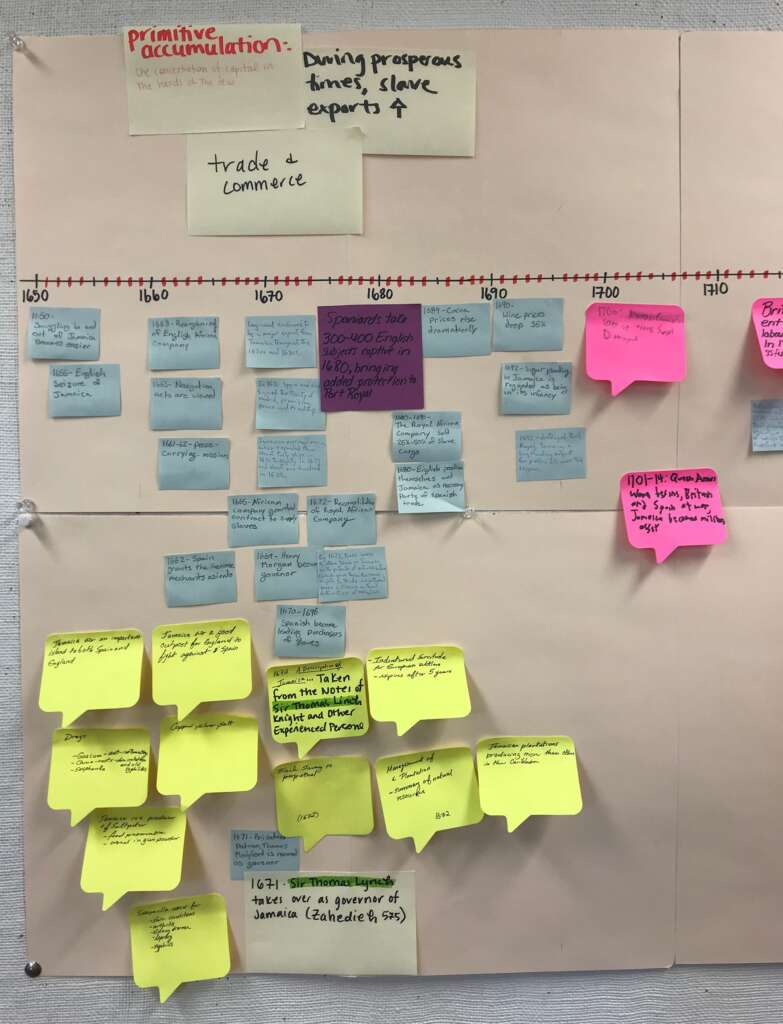

Set Up: Students were given four readings: two secondary sources (by historians), one primary historical source in prose, and one primary historical source in poetry. Students were asked to see all these texts as providing evidence for their timeline, even the poem. As a Notework assignment, the first version of their timeline was created outside of class, as a form of note-taking while they did the readings. Students were asked to develop a method of documentation so that they would know which dates came from which sources.

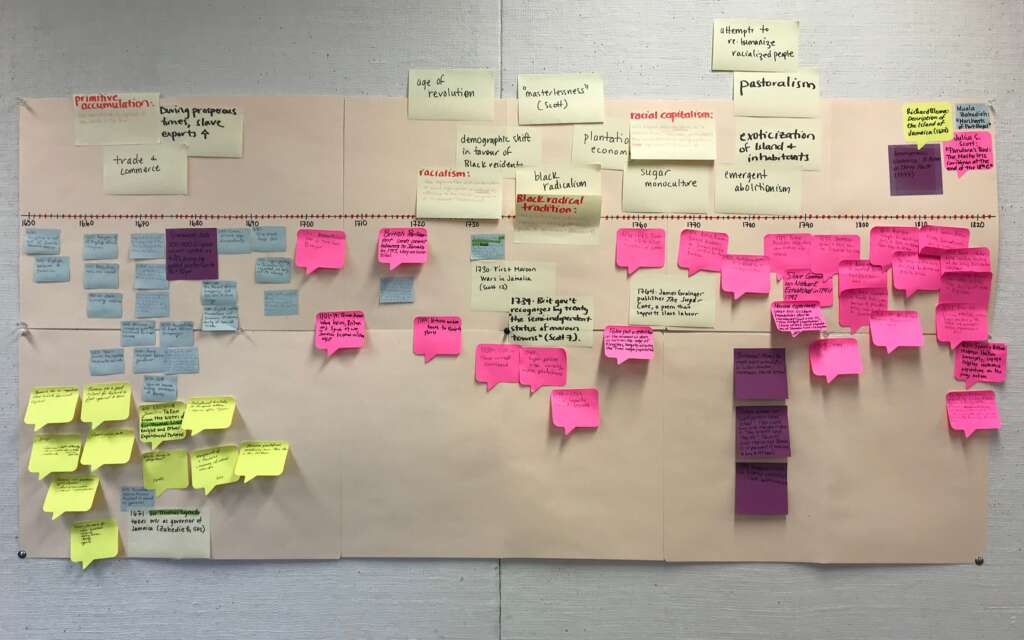

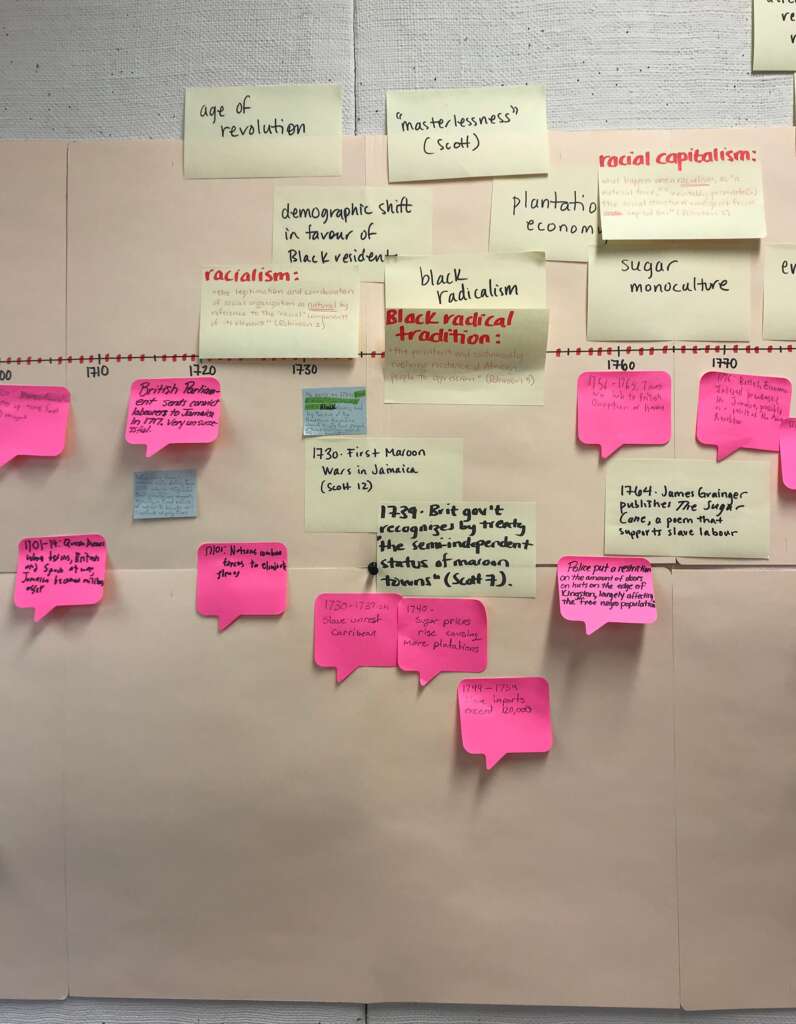

During class, students started in small groups by comparing and contrasting their timelines. I then gave each group a stack of four differently-colored sticky notes (one for each of the four readings), and asked them to be responsible for a specific date range, which they transferred onto the sticky notes based on their timelines. You can see the results above in yellow, pale blue, fuchsia and plum.

Coming together as a group, we discussed what the timeline had taught us so far, and I added a few more granular details that had been missed using the larger, pale yellow sticky notes, such as “1730: The First Maroon Wars in Jamaica” and “1764: James Grainger publishes The Sugar Cane, a poem that supports slave labor.”

The next stage of our discussion was to move from this granular level to a more conceptual one, and to do so by drawing upon the vocabularies we’d begun to develop in the previous week’s exploration of racial capitalism in Cedric J. Robinson. As a class, we began to “name” the higher levels, from “age of revolution” to “plantation economy,” “sugar monoculture” and “Black radical tradition”:

Outcomes: Working from an amount of “thick” history (derived especially from Nuala Zahedieh’s article “The Merchants of Port Royal, Jamaica, and the Spanish Contraband Trade, 1655-1692”) had the effect of introducing, indeed, subsuming students in a place and time about which they knew little coming into the course. Julius S. Scott’s article was also extremely valuable in this regard, both for sheer informational overload and for the way Scott himself names the conceptual levels (such as his idea of “masterlessness,” above, which one student suggested we add to the part of the timeline detailing slave revolts and the British government’s recognition of maroon towns in 1739).

As an activity for the second meeting of the term, this Notework assignment and in-class activity also set the tone for the remainder of our course. It brought into the foreground events that might have seemed to have been in the background if we had started with texts related to the second Agricultural Revolution or Industrial Revolution in Britain. It also asked us to work together to “name” the events at the conceptual level, connecting them to bigger conversations about, for instance, Marx’s so-called “primitive accumulation”:

Finally: For these reasons of foregrounding transatlantic history; destabilizing presumptions about white authorship; building shared knowledge and vocabulary; and inspiring camaraderie in the classroom, this is an approach to course design—supported by a specific take-home and in-class activity—to which I will return and continue to develop.